The dawn of the globalized age has left the world in a rather interesting state. While globalization has brought benefits to mankind, allowing nations to share technology and knowledge and thus helping it progress and prosper, it has also created some problems. Indeed, globalization has a darker side to it, represented by the negative forces which have been unleashed as a result of the very compression of time and space made possible by globalization itself. Within this dark side of globalization, there are many threats to the integrity of the current world order, but perhaps the crime with the most potential is trafficking. The whole continent of Europe represents the ideal hub for this crime, with several countries outside of its borders dealing with its market illegally.

The topic of trafficking in Europe has been covered previously in an analysis which can be found here. Out of the categories mentioned in the analysis, drug trafficking represents one of the more prevalent offences in the region. More specifically, opiate trafficking from Afghanistan into Europe is of particular interest. Towards the end of the 19th century, Afghanistan had become a major supplier of the drug to Western Europe, contributing to over 95% of Europe’s heroin supply. For having such a big influence over the continent, Afghanistan’s dealings within Europe is certainly an interesting case study to consider when talking about drug trafficking. As such, the following analysis will cover how exactly drug trafficking from Afghanistan into Europe has evolved in recent years, especially since the new millennium. However, before delving deeper into this topic, historical background will be necessary in order to fully understand Afghanistan’s ascension as Europe’s main provider of both opium and its opiate derivatives.

Afghanistan’s history with drugs

One of the main issues with drug trafficking is that there are various kinds of drugs circulating the markets, each having their own special effect on the consumer. When it comes to illicit trade and consumption, perhaps the most prominent kind is heroin, made from a natural substance found in the seed pod of the opium poppy plants, widely grown in Southeast and Southwest Asia. There are a few regions that are producing heroin for the rest of the world, those being Latin- America and the South of Asia. By far, Afghanistan is the world’s leading illicit opium producer. It has maintained its status since 2001, producing more than 90% of illicit heroin globally. Opium production in Afghanistan has become so fruitful that it provides jobs to over 400.000 nationals, with large portions of land being dedicated to the craft.

The country’s history of opiate production can be traced back to the mid-1950s, when it began cultivating poppy in significant quantities after Iran, its neighbor, had the practice banned. Following the disruption of supplies coming from the Golden Triangle, or the area where Thailand, Myanmar and Laos meet, Afghanistan increased its production of opium, becoming a major supplier of the drug to Western Europe and North America by the mid-1970s. During the Soviet invasion that began the Soviet-Afghan War of 1979, a number of resistance leaders concentrated their efforts on increasing the production of opium in their regions in order to finance their operations. Soon after, the United States got involved, helping the Afghan freedom-fighters known as the Mujahideen to cripple the Soviet Union slowly into withdrawal by aiding them in various ways. Thanks to this aid, many resistance warlords managed to broaden their production. By 1983, the amount of Afghan opium increased to 575 metric tons, doubling the amounts produced in the years prior. It was also during this time that Afghanistan’s reach in terms of drug trafficking expanded outside of its borders.

When the Soviet Army eventually withdrew in 1989, marking the end of its war with Afghanistan, a power vacuum was created. Infighting began among various Mujahideen factions to gain power and influence within the country. With the United States stopping their support in the region as well, their military existence was financed by cultivating poppy. Meanwhile, the region of Pakistan, another major opium producer in the continent, eradicated poppy cultivation within its borders during the 1980s, making the opium industry shift into Afghanistan. By the mid-1990s, during the Taliban rule, Afghanistan’s opium crop reached 4.500 metric tons, and Afghan poppy farmers shared a gross income of about US$1.3 Billion, divided among 200.000 families. However, Afghan opium producers encountered problems in 2000, when Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar started one of the world’s most successful anti-drug campaigns in collaboration with the UN, resulting in a 99% reduction in poppy farming in Taliban-controlled areas. As a consequence, about three quarters of the world’s supply of heroin was eradicated. This ban would remain effective for a short time, however, as it was lifted after the fall of the Taliban in 2002.

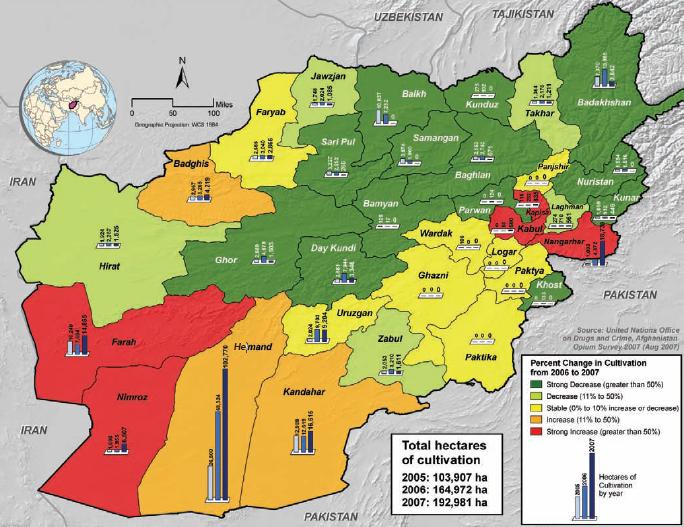

Following the United States’ invasion of the country as a consequence of the 11 September 2001 attacks, a number of prominent Afghans met under the umbrella of the UN. Their plans were to draft a new constitution and plan national elections for a potential reestablishment of the State of Afghanistan. Efforts to curb drug production and trafficking in the region were also set into motion, but due to corrupt officials who would take bribes in order to turn a blind eye to drug trading, those attempts were undermined. As a result, Afghan opium poppy cultivation saw an exponential rise as the years went on, shown in the map below. At this point in time, opium production and drug trafficking have become integral parts of Afghanistan’s economy. It was estimated in 2006 that a little over 50% of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) was generated by drug trafficking, and the production and sale of opium constituted the livelihood of some 3.3 million Afghans.

Europe: Afghanistan’s precious customer

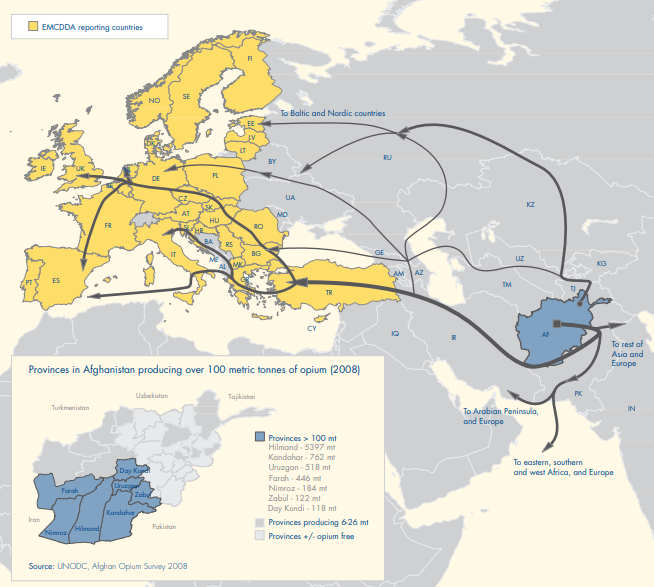

By 2008, Afghanistan has been Europe’s main heroin supplier for more than 10 years according to the EU agency that monitors drug and drug addiction. It continues to be as such, supplying heroin to the continent by two major land routes. The first one is the Northern route, from northern Afghanistan through Central Asia and on to Russia. The second one, and the one that will be of more interest is called the Balkan route. Through this route, the heroin leaves Afghanistan through Turkey, entering Eastern Europe and spreading throughout the rest of the land once it does so. This has been the main route for European drug trafficking for a long time, until the Northern route gained more traction in the mid-1990s. The map below shows the trafficking flows from Afghanistan to Europe through the two routes, and how they break and begin to spread throughout the continent once reaching it.

In terms of consumption, there are an estimated 1.5 million heroin users in the EU, with an average of 4 to 5 users per 1.000 of the adult population. In 2008, it was reported that Europe, without including Russia and Turkey, received 87 tons of heroin originating from Afghanistan. Of those, 60% was consumed in just four countries, those being the United Kingdom, Italy, France, and Germany. In addition, in order to ship the 87 tons in Europe successfully, Afghanistan must produce and send off about 140 tons of heroin. That is because of the high levels of seizures that occur on the way to the European continent, in the Islamic Republic of Iran and Turkey. In other words, a little over 60% of the heroin supply meant for Europe actually makes it in the region. Even with a little less than half of the supply lost, heroin still leaves a lasting effect in the continent, with about 5.000 deaths reported in 2008.

The organized crime groups involved in trafficking on the Balkan route are often composed of Afghan nationals or transit country citizens. However, because the goods very rarely travel the whole way from Afghanistan to Europe in a single unbroken journey, other actors not involved in the group that owns the drugs take part in the trafficking process as well. The drugs will be bought and sold by different parties along the route, and those will be further split and merged as they are moved closer to their destination. As complicated as the trafficking process may be, it is definitely worth the profits it generates. Afghan opiates generate more profit the farther the distance from the country of origin becomes. In Afghanistan, one kilogram of heroin is worth around US$2.000, rising to US$3.000 on its border with Pakistan, while it is marked at US$5.000 on its border with Iran. Moving on to Turkey, the price reaches US$8.000 per kilogram, allowing the groups who carry out the trafficking between Afghanistan and Turkey to make anywhere between US$450 Million and US$600 Million per year. In addition, the UNODC Report from 2010 estimated that the annual retail value of Afghan heroin moving to Europe through the Balkan route was roughly US$20 Billion, making the crime of trafficking heroin one of the most profitable in the continent.

With it generating so much money, it comes to no surprise that producers in Afghanistan are seeking to develop their craft even further. The total area of opium poppy plantations from which opium is produced has risen steadily each year since 2010, going from 123.000 hectares to over 224.000 hectares in 2014, reaching an all-time high in 2017, with 328.000 hectares dedicated to the plant. When considering that in 2017, the total area under opium poppy cultivation worldwide was comprised of about 420.000 hectares, it meant that Afghanistan held 75% of the world’s opium plantations. Being tied to the cultivation area, the amount of opium produced has risen as well as the years went on. In 2010, the country produced about 6.900 tons of opium, the amount increasing by roughly 650 tons by 2014, when 7.550 tons were produced. In 2017, an astonishing 9.000 tons of opium were produced, enough to rival almost 3 Saturn V rockets.

Seeing as the cultivation and production of opium continued to grow from one year to another, it should come to no surprise that little is being done to curb such developments. Because the production of this drug accounts for the livelihood of millions of Afghan people, increased government involvement in the matter would be met with public unrest. External actors are not doing much to help either, as tons of opium and opiates escape the trafficking routes outside of Afghanistan and get into Europe. As a result, the total area of opium poppy plantations that is eradicated yearly has shrunk. After experiencing a rise between 2010 and 2013, from around 2.300 hectares to roughly 7.000, from 2014 onwards it would drop significantly, with only 2.692 hectares eliminated that year, an over 60% drop. By 2018, this eradicated area was only comprised of 406 hectares, a nearly 94% decrease when compared to what the authorities achieved in 2013.

Despite those disappointing numbers, 2018 saw a decline in Afghan opium poppy cultivation to 263.000 hectares. However, this was only the case when compared to the previous year’s area of 328.000 hectares, making 2018 figure the second highest on record. What is even more worrying is that the area of poppy cultivation shrunk so much between 2017 and 2018 because of a drought, not because of local authority action. Had the weather conditions been better, it is highly possible that Afghanistan would have maintained its large plantations, if not widened them further. Despite the unfavorable weather conditions and the shrinking plantation area, the country still produced 6.400 tons of opium.

It is also important to note that the drugs produced from that year’s Afghan crops have already entered international markets, and a large percentage is being consumed in Europe thanks to the trafficking done on the still-prominent Balkan route. In fact, the Balkan route has essentially become the main route for opiate trafficking from Afghanistan by 2017, due to a decline in trafficking along the Northern route. This fact can be observed by the number of seizures done along the route, which has significantly dropped. Nearly a decade prior, in 2008, the amount of opiates intercepted along the Northern route represented 10% of the global amount seized, whereas in 2017 it had fallen to barely 1%. That could be because the demand along that route shifted to synthetic drugs, changing the nature of the market. As for the Balkan route, the opiate amount seized along the way rose, accounting for 47% of the global quantities intercepted in 2017. While the number of seizures done may not be definitively indicative of the prominence of a trafficking route, it does show what the drug quantity that is being trafficked along it in the first place may be. As such, more seizures imply bigger drug quantities, while less seizures imply smaller such quantities passing through that route.

Despite the high number of seizures along the Balkan route, opiate trafficking remains a profitable crime. In 2014, the total monetary value of illicit opiates trafficked on the Balkan route rose by US$8 Billon since 2010, bringing an impressive US$28 Billion per year to the ones involved. To put it differently, this sum is roughly a third bigger than the entire GDP of Afghanistan in 2014, estimated at about US$21 Billion. Considering that this is only a part of the value generated by the opiates trafficked from Afghanistan, the total profits brought in through the other routes and markets would make an even bigger figure. Nevertheless, it would be important to note that the profit made from illicit opiates that actually remains in Afghanistan is only a fraction of this sum. That is because of the other parties involved in Afghan opiate trafficking, who take a cut themselves, and the rise in price per kilogram the further away the drug moves from Afghanistan, as highlighted above. Therefore, while the market value of the whole global opiate trafficking process exceeds Afghanistan’s GDP, it only accounts for an eighth of it nationally. This shows how Afghanistan is just one part of a much bigger issue, despite doing most of the work by being the cultivator, producer, and initial trafficker of the illicit good.

The future prospects of Afghan opiate trafficking

Having seen the recent evolution of Afghanistan’s opium production and trafficking, it is clear that, regardless of the amount, there are still thousands of tons of opium being trafficked in Afghanistan’s primary market of Europe each year and officials are not doing enough to stop this. As the years go on, the crime of opiate trafficking from Afghanistan into Europe will continue to evolve further. The potential establishment of cooperation among law enforcement authorities in Europe through organizations such as Europol can only truly achieve so much. As long as there is a demand for those trafficked goods, criminals will find a way to continue their practices. This is especially easy to achieve in today’s globalized world, which has connected and technologically enabled the world market, allowing criminal groups to exploit opportunities that arise within it. As a result, drug availability within Europe remains commonplace as consumers have access to a wide variety of highly pure and potent products at accessible prices.

With the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic, which has caused an economic downturn, with rising unemployment and lack of opportunities associated with lockdowns, people may get involved in drug trafficking in some way. The poor and disadvantaged people that have been put in those positions thanks to the Coronavirus will be likely to engage in harmful patterns of drug use in order to cope with their situation. Some may even turn to illicit activities linked to drugs, such as production or transport. Knowing this, perhaps what authorities need to start considering is how to change the mindset of those who encourage and demand the continuation of this crime. Otherwise, drug trafficking of any sort, not just Afghan opiates, will continue well into the future.